Can a Child Get Ptsd From Multiple Divorces in Family

Abstract

Parental conflicts consistently predict negative outcomes for children. Enquiry suggests that children from high-disharmonize divorces (HCD) may besides experience post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), yet lilliputian is known about the association between parental conflicts in HCD families and kid PTSS. We investigated this association, hypothesizing that parental conflicts would predict kid PTSS. Nosotros as well tested the moderating role of interparental contact frequency, hypothesizing that frequent contact would intensify the association between parental conflicts and child PTSS. This study was role of an observational report on the outcomes of No Kids in the Middle (NKM), a multi-family group intervention for HCD families. A total of 107 children from 68 families participated in the written report with at least 1 parent. Nosotros used pre- (T1) and post-intervention (T2) information. Research questions were addressed cross-sectionally, using regression analyses to predict PTSS at T1, and longitudinally, using a correlated change (T1 to T2) model. The cross-sectional findings suggested that mother- and child-reported conflicts, but not begetter-reported conflicts, were related to the severity of child PTSS. Longitudinally, we found that change in male parent-reported conflicts, but non alter in kid- or mother-reported conflicts, were related to change in kid PTSS. The estimated associations for the different informants were not significantly dissimilar from one another. The frequency of contact betwixt ex-partners did not moderate the relationship betwixt parental conflicts and child PTSS. We conclude that in that location is a positive association between parental conflicts and child PTSS in HCD families contained of who reports on the conflicts.

In the Netherlands, about 86.000 children are involved in a divorce each year (Ter Voet, 2019). Although most parents can handle the aftermath of these divorces reasonably well, 4% to 25% of the divorces involve ongoing bitter conflicts (Fischer et al., 2005; Qu et al., 2014; Smyth & Moloney, 2019). This type of divorces is called a high-conflict divorce (HCD) and is characterised by pervasive negative exchanges between ex-partners in combination with an insecure and hostile emotional environment. Ex-partners are entrenched in pervasive negative interpersonal dynamics, which are characterised by arraign, hostility, anger, and fixed negative perceptions of each other (Anderson et al., 2011; Smyth & Moloney, 2019).

Parental conflict consistently predicts negative outcomes for children (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010; van Dijk et al., 2020). Child negative outcomes may be even more pronounced when parental conflicts consist of high levels of hostility or aggression, are kid-related (the disputes are about the children), or when the parents involve their children in their conflicts (triangulation), which is most likely to happen in HCD disputes (Hetherington, 2006; McCoy et al., 2013; Van Dijk et al., 2020; Van Eldik et al., 2020). Information from a contempo study showed that children involved in high-conflict divorces may exist at an increased risk of developing a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with almost half (46%) of the children beingness at an increased risk for developing PTSD (van der Wal et al., 2019). This percentage is not far below what has been observed for other types of traumatic experiences in childhood. For example, 67% of children exposed to interparental violence (Georgsson et al., 2011) and 53% of children who were clinically referred subsequently experiencing 1 or more traumatic events (Verlinden et al., 2014) reported an increased risk for developing PTSD.

The report by van der Wal and colleagues (2019) is the only study, as far equally we know, that has investigated the hazard of PTSD in children from HCD families. Despite the current relative lack of data to support it, scholars have voiced their concerns regarding the potential bear upon of HCD on the development of PTSD in children (Davidson et al., 2014). Although research on PTSD in HCD families is lacking, at that place is a vast torso of research on the damaging effect of interparental violence (IPV) on PTSD. A meta-assay showed that IPV has a large consequence on PTSD (Evans et al., 2008) and recent enquiry suggests that IPV tin can predict PTSD even into young adulthood (Haj-Yahia et al., 2019). IPV occurs when children hear, run across, or are direct involved in physical or sexual assaults betwixt their caregivers or parents. In HCD families, children repeatedly hear, run across or are involved in verbal conflicts. The first aim of the current study was to examine whether parental conflicts are related to child post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in this HCD context.

Although IPV can have long-lasting effects on children, there is some prove that decreases in IPV or parental conflicts may also have a positive effect on the children. Several studies have shown that increases in marital conflict were associated with increasing depressive symptoms and rule-breaking behavior in adolescents, whereas decreasing marital conflicts were associated with decreases of depressive symptoms and dominion-breaking behavior (El-Sheikh et al., 2019; Madigan et al., 2017). This latter consequence is promising and hopeful, as information technology suggests that interventions focusing on diminishing parental conflicts may have a straight positive affect on child well-being. It is not yet known whether child PTSS might also be related to changes in IPV or parental conflicts.

There is, notwithstanding, some enquiry on how changes in trauma-eliciting situations might affect PTSD. For example, a study among asylum-seeking children showed that children whose asylum application had been accepted showed fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms at follow-up than children whose application had been rejected (Müller et al., 2019). Although change was not directly tested, their information do propose that children whose application was accustomed experienced a decrease of their PTSS, whereas the other children did not. This report implies that the level of PTSS can exist afflicted by changes in the trauma-eliciting situation and that PTSS might decrease if some aspects of the traumatic event are decreased or are taken abroad. The current study explored whether similar processes are present in HCD families by not merely investigating the relation between parental conflicts and kid PTSS concurrently, but also longitudinally.

Interparental Contact

One potentially important aspect of the trauma-eliciting situation in HCD families is the frequency of interparental contact. Enquiry has shown that ex-partners with children are more likely to persevere in their conflicts than ex-partners without children. The shared responsibleness for the children condemns ex-partners to continued interactions over time (Fischer et al., 2005). Indeed, HCD parents have described their interparental encounters concerning child arrangements to be highly stressful to them (Target et al., 2017). Frequent contact may even exacerbate parental conflicts; Kluwer (2016) showed that ex-spouses' unforgiving emotions were related to college levels of conflict when the contact frequency was high. It thus may do good the children if parents can reduce their encounters to a minimum, without necessarily decreasing parent–child encounters, every bit warm parent–child contacts with both parents may be beneficial for kid well-being (e.thousand., Harper & Fine, 2006; Nielsen, 2017). Unfortunately, niggling is known about the event of the frequency of interparental contact. We tested whether interparental contact frequency moderates the relationship between parental conflict and child PTSS. We hypothesized that parental conflicts have a stronger touch on upon child PTSS when the level of interparental contact is high.

The Current Written report

The current study aimed to make full a gap in the literature by studying intergenerational spillover from parental conflicts to kid PTSS in the context of HCD families. The current written report only included families without current IPV. Although a previous report on this sample (van der Wal et al., 2019) has found that PTSS is high for children in HCD families, this study extends these findings past investigating the office of disharmonize; studying whether the severity of and change in child PTSS is related to the severity of and change in parental conflicts. This was done by analyzing whole families (children and both parents) meantime and longitudinally (over 2 time points). Moreover, we studied the moderating office of interparental contact frequency. The frequency of contact between ex-partners may exacerbate the effect of conflicts on child PTSS. Research then far has non paid much attention to the frequency of interparental contact.

The electric current newspaper is role of a larger multi-moving ridge study on the outcomes of No Kids in the Centre (NKM), a multi-family group intervention aimed at diminishing and de-escalating parental conflicts and developing constructive communication regarding the children (Visser & van Lawick, 2021). The current written report had two aims. First, nosotros tested whether parental conflicts predicted child PTSS in a sample of HCD families participating in the intervention NKM. Second, we tested whether this issue was moderated by the frequency of interparental contact. We tested this both concurrently (at the get-go of the intervention) and longitudinally (studying the alter between the outset and end of the intervention). This led to the post-obit hypotheses:

-

H1: Parental conflicts are related to child PTSS at the offset of the intervention.

-

H2: Parental conflicts are related more strongly to child PTSS when interparental contact frequency is high than when interparental contact frequency is low (i.due east., moderation of contact frequency).

-

H3: Modify in parental conflicts between the start and stop of the intervention is related to modify in kid PTSS.

-

H4: Modify in parental conflicts betwixt the get-go and end of the intervention is more than strongly related to change in child PTSS when interparental contact frequency is high than when interparental contact frequency is low (i.eastward., moderation of contact frequency).

Parental conflicts were measured from the perspective of both parents, besides every bit from the perspective of the child.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Families participating in the NKM intervention between April 2014 and March 2016 were asked to participate in the study. All families were referred by judges or kid protection services (CPS) to a health care institution because the wellbeing of the children was threatened by the ongoing parental conflict. A total of 302 parents were asked for their participation of whom 203 (67%) signed the informed consent. Of these 203 families, 24 did not participate in the research and another twelve decided not to start or to discontinue the intervention, resulting in a sample of 167 parents participating in the written report (55% of the 302 parents who were approached). There were 56 couples and 55 parents participated alone. Only parents whose children participated in this study, were included in the analyses for this manuscript. Assessments took identify at the start (T1) and (T2) end of the intervention, which was approximately four months apart.

Children between vi and 18 years old could participate in the inquiry if both of the legal parents signed for consent. Children of 12 years and older also had to sign the assent form themselves. In total, 193 children were invited to participate, of which 144 children received and gave permission (75%). As the questionnaire regarding PTSS was designed for children of 8 years and older, younger children were excluded for this particular manuscript (n = 28). For some other 9 children, none of the parents provided data in the study. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 107 children betwixt 8 and 18 years old in 68 families. All children participated with at least one parent. The sample consisted of 35 families with one participating child, 27 families with two participating children and six families with 3 participating children. Of the 68 families, 49 families had both parents participating in the report, meaning that near children (70%, n = 75) were participating in the report with both of their parents. Families took office in the intervention across 14 different institutions in 24 different intervention groups.

Intervention

No Kids in the Middle (NKM) consists of viii parallel parental and children group sessions of maximal six parental couples (over a period of approximately four months). To exist admitted, both parents need to participate in the intervention. At the same fourth dimension, children groups have identify, consisting of all children aged 4 to 18 years that are involved in the HCD divorces of the parents in the intervention. The children groups primarily focus on support and empowerment. Research shows that parents participating in NKM reported decreased parental conflicts upwards to half dozen months post-intervention (Lange et al. submitted; Visser et al. 2020). The presence of IPV was an exclusion criteria, significant that none of the families had ongoing IPV during the study.

Measures

PTSS

Children's traumatic touch on of the high-disharmonize divorce of their parents was measured with the Children'southward Revised Touch on of Event Calibration (CRIES-13; originally developed by Horowitz et al., 1979; translated to Dutch by Van der Ploeg et al., 2004), which provides a stable assessment of traumatic impact across different types of trauma and life threatening events (east.m., Perrin et al., 2005) and has been found to be reliable and valid (Verlinden et al., 2014). Children rated 13 items assessing the frequency of the occurrence of these events in the past week in relation to the conflicts and divorce of their parents (i =never, 2 =rarely, iii =sometimes, and four =often). Case items are: "Exercise you recollect about the divorce and conflicts of your parents even when you don't hateful to?", and "Exercise yous avoid talking about the divorce and the conflicts of your parents?" Nosotros used the sum score as an indicator of traumatic impact (ranging from 0 to 65). A score of xxx and greater has been suggested equally the almost efficient cutting-off for discriminating heightened take a chance for PTSD (Verlinden et al., 2014). In our sample, 46% of the children had a heightened adventure for PTSD at T1 and 34% at T2. Reliability of the scale was skilful based on Guttman's lower bound (λ 2 = 0.87 at T1 and λ 2 = 0.xc at T2; Guttman, 1945).

Conflict, Parent-reported

Every bit co-parenting disharmonize (i.e., the caste to which parents agree or disagree nearly kid-related problems) is one of the near devastating types of conflicts for children (Van Eldik et al., 2020), we specifically focused on co-parenting conflicts for the parent-reported conflicts. Parental perception of co-parenting conflict was measured using the co-parenting conflict scale from the Psychological Adjustment to Separation Test (By; Sweeper & Halford, 2006; translation past De Smet et al., 2012). The calibration consisted of seven items on a 5-point scale (one =totally disagree, five =totally concord). Example items are "My former partner and I conform child visitation well" (reversed) and "I fight with my onetime partner over the well-being of the kid/children". Higher average scores (range = 1–5) indicate higher levels of co-parenting disharmonize. Father-reported and mother-reported conflicts were used independently in the analyses to allow for studying all family members' perspectives. Reliability of the calibration was expert based on Guttman's lower bound (λ two varied between 0.75 and 0.84 over time for men and women).

Conflict, Child-reported

Children reported to what extent their parents fought in their presence (one item) on a 5-point scale (ane =never, two =sometimes, 3 =regularly, iv =frequently, and 5 =always).

Frequency of Contact

Frequency of contact was assessed through three questions completed past the parents, namely 'How frequently exercise you talk to your ex-partner personally?', 'How oft do you talk to your ex-partner through the phone?' and 'How oft do you have written contact with your ex-partner?' All three questions could be answered on a five-indicate scale (ane =(almost) never, ii =less than one time a month, 3 =one time a calendar month, iv =several times a month, 5 =more in one case a week). Clinical experience of the second author indicated that children might not only exist stressed when their parents actually see one another personally, but besides be stressed by interparental telephone and text contact, for example if the sound of incoming text messages is always followed by acrimony and distress of the parent. Nosotros therefore decided to take all these different types of interparental contact into business relationship by calculating the average of these three questions. We did non analyse parents separately, but rather used an average of mothers and fathers as the closest representation of the actual contact frequency between parents. A higher score (range = i–5) indicated a higher frequency of contact (independent of the medium). Reliability of the scale was practiced based on Guttman's lower bound (λ two = 0.86 at T1 and λ 2 = 0.87 at T2).

Analytical Plan

Missing Data and Nesting of Information

We experienced non-response at both fourth dimension-points, with dissimilar rates of non-response for the unlike informants. Not-response at the outset of treatment was i% for the children and 15% for fathers and 15% for mothers. Non-response at the finish of treatment was sixteen% for children, 41% for fathers and 32% for mothers. All children had information of at least one parent at the start and 85% had data of at least one parent at the end of handling. There were no missing information for age and gender of the child. For the remaining variables, available data ranged betwixt 77 and 85% at T1, and between 55 and 77% at T2. A quarter of the families (27%, n = 29) had complete data (no missing data on any of the assessments for any of the family members). These families did non differ on any of the variables from families with partially missing data, except for PTSS at the offset of the intervention, which was lower for families with complete data compared to families with partially missing information (t (88) = ii.lx, p < 0.05). To account for missing data, all information was imputed 40 times using Bayesian interpretation in Mplus, using an unrestricted (H1) variance–covariance 2-level model (children nested in families) (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010; Graham et al., 2007).

All analyses were conducted in Mplus eight (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Nosotros accounted for the non-independence of families by adjusting the standard-errors using the COMPLEX module in Mplus. For conflict, separate analyses were run for each informant (father, mother and child), as we were interested in these dissimilar perspectives. For contact frequency, the average of both informants (fathers and mothers) was used to summate the amount of contact between parents at that time-signal as an estimation of the actual contact frequency betwixt parents. Prior to all analyses, nosotros checked the bivariate correlation matrix. Historic period and gender of the child were included as covariates in subsequent analyses if they were significantly correlated (p < 0.05) to 1 of the included variables.

Result of Conflict on PTSS at Start of the Intervention (H1) and Moderator Effect (H2)

We tested conflict as predictor of PTSS using three hierarchical linear regression analyses (as we had three disharmonize informants). We added contact frequency in the 2d step and an interaction term betwixt contact frequency and conflict in the third footstep. The interaction term was included to examination for moderation of contact frequency (H2). All included variables were assessed at T1. As these models were saturated, they had a perfect fit and model fit was not reported.

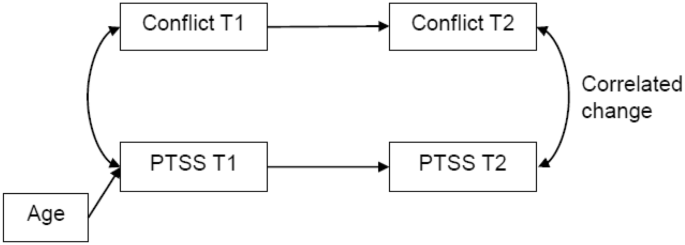

Correlated Change (H3) and Moderator Effect (H4)

We tested whether change in conflict and change in PTSS during the intervention were related to one another. Although we planned to use correlated latent modify models, model fit for these models was poor. We therefore cull to use a path model whereby T2 of both conflict and PTSS were regressed on T1 of the same variable. We too included an association between both variables at T1 and T2. The association at T2 can exist interpreted as correlated change (Asendorpf & van Aken, 2003). Effigy ane provides a graphical representation of the tested model.

Diagram of analytical model, representing the correlated change between conflict and PTSS between T1 and T2

We subsequently tested whether frequency of contact was a moderator using multi-group analyses. For this purpose, we split the families into 2 groups: one group that reported an increment over time of the intervention in contact frequency (59%) and one grouping that reported a decrease over time in contact frequency (41%). Using the Satorra and Bentler (2001) scaled chi-squared divergence exam, nosotros tested an unrestricted model against a model in which all parameter estimates were restricted to be equal across these ii contact groups. As the number of families in each group varied across the imputed datasets, it was non possible to conduct these moderator analyses on the imputed data. Therefore, the moderator analyses were conducted on the original non-imputed data. The due north used in these analyses varied betwixt 76 and 88 (71% to 82% of the full sample).

Sensitivity Analyses

Although all families were referred because of the ongoing parental conflicts, some families had only recently separated. Divorcing couples are likely to have more than severe conflicts just after separation due to the stress of the new situation, only these may not be enduring for multiple years, as is the case in HCD families (Smyth & Moloney, 2019). We therefore replicated all analyses for the subset of families that had separated for more than 2 years (n = 89) to exclude families that potentially had situational rather than persisting parental conflicts. Nosotros only reported the results of these sensitivity analyses if they differed from the original analyses on the full sample.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all variables. Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. There was a moderate correlation between fathers' and mothers' disharmonize reports, all the same only weak and sometimes not-significant correlations betwixt children and parents. Interestingly, contact frequency was negatively related to the level of conflict according to parents, only non related to the level of conflict according to the children. Thus, parents reporting college levels of conflict tended to report lower levels of contact and vice versa. This association was significantly stronger for mothers than for fathers at T2 but non at T1. The corporeality of conflict reported by children, however, was not related to the frequency of contact between parents. Kid'southward age was correlated to their level of PTSS and was therefore included as covariate in all analyses. Gender was merely significantly related to the level of co-parenting disharmonize according to the mother and was therefore only included as a covariate in analyses regarding mother-reported conflicts.

Outcome of Conflict on PTSS at Start of the Intervention (H1) and Moderator Upshot (H2)

We offset tested hierarchical linear regressions with child PTSS at T1 equally the dependent variable (run across Table 3). The level of parental conflicts, as perceived by the mother and the child predicted PTSS; more conflicts were related to higher PTSS. Male parent-reported parental conflicts were not related to PTSS. The estimates for the three informants were non significantly different from ane another. When adding contact frequency, mother- and child-reported disharmonize continued to predict kid PTSS. Contact frequency did non predict child PTSS, nor did the interaction between contact frequency and conflict predict kid PTSS. Thus, our results propose that contact frequency did not moderate the clan between conflict and child PTSS.

In the sensitivity analyses, just including families that had separated for more than two years, the level of conflicts co-ordinate to children was no longer a significant predictor of child PTSS (B (s.e.) = 2.fourscore (one.50), p = 0.06).

Correlated Change (H3) and Moderator Effect (H4)

Secondly, we tested the correlated modify between parental disharmonize and child PTSS. For all models, model fit was excellent (meet Table 4). For father-reported disharmonize, alter in conflict was positively related to change in PTSS, indicating that decreasing levels of disharmonize were related to decreasing levels of child PTSS (B (southward.e.) = ii.84 (1.06), p = 0.01). Change in child- and mother-reported conflict was not significantly associated with alter in child PTSS (kid-reported disharmonize: B (s.e.) = 2.40 (1.35), p = 0.08; mother-reported conflict: B (southward.e.) = 0.65 (0.87), p = 0.45). Again, all the same, the estimates for the three informant groups were not significantly different from one another.

Before conducting the multi-group analyses on the original non-imputed data to test for moderation of interparental contact frequency, we replicated the path models on the original data. The findings replicated the results of the imputed datasets regarding the event of parental conflict on kid PTSS (male parent-reported disharmonize: B (s.east.) = 4.42 (1.23), p = 0.000; kid-reported disharmonize: B (s.east.) = 2.52 (i.26), p = 0.05; female parent-reported disharmonize: B (s.e.) = 1.22 (0.77), p = 0.11). When conducting the multi-grouping analyses on the original data, nosotros found that the restricted model, in which all parameters were restricted to be equal beyond the two groups representing increasing or decreasing levels of contact, was non significantly dissimilar from the unrestricted model in all analyses. This means that contact frequency was not a significant moderator.

Give-and-take

The aim of this study was twofold. First, nosotros tested the association between parental conflicts and child PTSS, concurrently and longitudinally, assuming that parental conflicts would be positively associated to child PTSS. Concurrently, we plant that both female parent- and kid-reported conflicts, but not father-reported conflicts, were related to the severity of the PTSS. Longitudinally (between the start and end of the intervention NKM), change in father-reported, only not female parent- or kid-reported conflict, was related to change in child PTSS. Secondly, we examined the moderating part of interparental contact frequency, hypothesizing that more frequent contact might intensify the association between conflict and PTSS. This hypothesis was non confirmed; interparental contact frequency did not moderate the association betwixt disharmonize and PTSS.

The current report showed a robust association between parental conflicts and child PTSS in HCD families, as these findings were found for multiple informants, were replicated in most of the sensitivity analyses, and were establish using two dissimilar analytical approaches. Every bit far as we know, this is the get-go time that child PTSS has directly been related to parental conflicts in HCD families. Since IPV was an exclusion criteria for participation in the intervention, this study provides testify that verbal conflicts, without IPV, may also be associated to kid PTSS. It is of import for practitioners to be attentive to PTSS in children of divorcing couples, especially when parental conflicts are severe. Although parental conflicts may not be the simply gene of a divorce that can be stressful for children (eastward.g., moving houses, losing contact with friends or family), the ongoing and astringent conflicts are likely to be an important attribute of the divorce trauma in HCD families. It is known that prolonged traumatic stress or accumulation of traumatic events tin increase the risk of PTSD (e.yard. Müller et al., 2019), withal less is known nigh the link between decreases in the trauma-eliciting event and subsequent changes in PTSS. In this study, conflicts decreased on average, suggesting that decreases in parental conflicts may be related to decreases in PTSS. Moreover, as parental conflicts, but not child PTSS, were directly targeted by the intervention, these results cautiously suggest that decreases in parental conflict can lead to decreases in child PTSS. This adds to the preliminary available evidence that taking abroad or diminishing part of the trauma-eliciting event can have a direct positive bear upon on PTSS. Nosotros must, all the same, carry in heed that this was a correlational study, and hence, causation cannot be tested. It is equally likely that changes in kid PTSS led to changes in parental conflicts. For case, parents in HCD tend to fight for the do good and the expert of their children (Anderson et al., 2011; Target et al., 2017). Perceiving PTSS in their child might exist a reason for parents to intensify conflicts with their ex-partner, bold that their ex-partner is the cause of their child'due south distress.

Although the results were somewhat different for different informants (i.e., mother-reported and child-reported conflict were related to child PTSS at the start of the intervention, whereas father-reported change in disharmonize was related to alter in kid PTSS), the results did non significantly differ between informants, suggesting that, overall, father-, mother- and kid-reported conflict had a similar relation to child PTSS. Previous research has plant that conflicts may have a more severe bear upon on children through fathers than mothers (Cummings et al., 2010). Parenting behavior is an of import mediator through which parental conflicts impact children (van Dijk et al., 2020). Several studies suggest that the spillover effect from parental conflicts to parenting behaviors, such as parental distress or parent–child hostility, is stronger for fathers than for mothers (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cummings et al., 2010; Harold et al., 2013). According to the fathering vulnerability hypothesis, fathers might be more vulnerable to experience matrimony-related disruption in their parenting than mothers because the distinction between their roles of husband and father might be less distinct (Cummings et al., 2010). Not all studies, all the same, find back up for this notion of vulnerability; studies have reported that parents either have similar furnishings on children or that mothers and fathers affect children differently through unlike mechanisms (e.m., Nelson et al., 2009; Ponnet et al., 2013). The current study adds to this body of bear witness, suggesting that both parents take equal effects on their children.

Child-reported conflict was no longer a significant predictor of kid PTSS in the sensitivity analysis, suggesting that child-reported conflict might exist a less robust predictor of child PTSS in families with enduring and long-lasting conflicts. The kid-reported conflicts were assessed with only a unmarried item, assessing the frequency with which parents had conflicts in forepart of them. In HCD families with indelible conflicts, the actual frequency of conflicts in the child's presence might be less of import than the destructivity of the conflicts, or how the conflicts affect the children through other processes such as parenting behaviors.

Reverse to our hypothesis, we did not detect a moderating result of interparental contact frequency. Although unexpected, this finding is consequent with a related study on interparental contact frequency and child wellbeing after divorce. Kluwer (2016) showed that parental revenge motivations in divorced parents were positively associated with parental conflicts, which, in plow, were negatively associated with kid well-being. This association was not moderated past interparental contact frequency. Although Kluwer (2016) studied child well-beingness rather than child PTSS, she used the same measure to appraise interparental contact frequency. Thus, research so far seems to propose that interparental contact may not intensify the association between conflicts and kid outcomes. This does, however, not mean that interparental contact is of no relevance for parental conflicts or child outcomes. Reducing contact with the ex-partner may be a tactic parents use to reduce their conflicts with their ex-partner. NKM therapist may also encourage ex-couples to reduce their interparental contact frequency if reducing the conflicts through other means seems especially hard.

Indeed, the bivariate correlations of this study showed that frequent interparental contact was related to lower rather than college frequencies of conflict. This suggests that parents reporting many conflicts may endeavor to avoid contact with their ex-partner. It is interesting that this result was stronger for mothers than fathers. This could exist because of the more than 'secure' position of mothers, as they are more oft the primary caregiver of the children after divorce (Kalmijn, 2015). This was also the case in our report, where twoscore% of the children lived primarily with their mother compared to only vi% of the children living primarily with their father. As such, mothers can more easily decrease contact with their ex-partner without this having whatsoever consequences for the frequency with which they meet their children. Fathers, on the other mitt, may need to 'fight' for the right to see their children (Target et al., 2017), which means they might be more than inclined to proceed in touch with their ex-partners. Over time, conflicts seemed to decrease, whereas contact frequency slightly increased, suggesting that ex-partners may also increase their contact if their interactions better over fourth dimension.

This study has several limitations. Start, we simply had data for two time points, relatively shut in time to one another (four months). Replicating and extending our findings in longitudinal studies with more time points would exist a promising avenue. Longitudinal observational studies could investigate how parental disharmonize and child PTSS co-develop and mutually influence ane another over time. Alternatively, an RCT of an intervention addressing parental conflicts would allow to test causality and study whether an intervention can decrease kid PTSS by reducing parental conflicts. A second limitation is the employ of self-reports instead of observation of conflicts. Parents' perception of the conflicts may not align with actual levels of parental conflicts, which may blur the human relationship between parental conflicts and child PTSS. This is exemplified by the moderate correlation between fathers' and mothers' perception of their mutual conflicts. Nevertheless, our findings were not significantly different betwixt informants, suggesting that parental conflicts are related to kid PTSS contained of who reports on the conflicts. Lastly, although our focus was on conflicts, many other aspects of a divorce may be stressful for children, such as moving houses, courtroom involvement, reduced income of the parents, or the sudden loss of their secure family as a basis (Amato, 2010). Besides child maltreatment or interparental violence may play a role in HCD families and impact upon child PTSS (Beck et al., 2013). Future enquiry into child PTSS in the context of HCD needs to pay attention to these other aspects to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the feel of HCD for children and the part of the parental conflicts inside this context.

It is important to notation we had to utilize a unlike analytical approach than originally planned for our analyses of correlated alter due to poor model fit. Although the path model used may be less intuitive for the analysis of correlated change than the latent modify model, both the path model (Asendorpf & van Aken, 2003) and the latent change model (Könen & Auerswald, 2021) are appropriate for assessing correlated modify and produced very like estimates. We therefore do non feel this shift in belittling arroyo has impacted upon the trustworthiness of the results.

This report also has several strengths. Kickoff, we used a multi-informant and systemic approach, investigating parental conflicts through the eyes of both parents, too as the children involved, and looking at an intergenerational spillover effect. Second, nosotros included a large historic period-range (viii–18 years) and an equal number of boys and girls in the report, and we controlled for age and gender in the analyses, allowing these results to be generalizable to a big grouping of children in HCD families. 3rd, we managed to include the fathers of 85% of the children in this study. Although fathers' behavior and characteristics are related to children's normal and abnormal development, fathers are underrepresented in child psychopathology research (Parent et al., 2018), as well as in therapeutic handling of children'south mental health (Tully et al., 2017). The current study institute some differential results for fathers and mothers, supporting the necessity of including and studying the role of fathers in children'southward mental health. Last, this study was novel in its analyses of interparental contact frequency. For this purpose, we used an inclusive measure, assessing all types of contact, namely face-to-face, phone and written contact.

Clinical Implications and Conclusions

The high level of PTSS observed in this sample of children from HCD families underlines that professionals working with these families need to be sensitive to potential child PTSS. Incorporating a trauma narrative into an intervention can strengthen children processing the traumatizing events they may take been exposed to past growing up in HCD families (Cohen et al., 2012). The current study further suggests that professionals need to carefully observe the relationship betwixt the interparental contact frequency and the parental conflicts within each family unit. Although reducing contact may be a strategy to reduce disharmonize, nosotros constitute that low contact was actually related to high levels of conflict. Every bit causality could not be tested, nosotros do not know whether parents with frequent conflicts avoid one another, or whether avoidant parents get into more conflicts due to a lack of communication. Lastly, NKM seems to be a promising intervention; preliminary evidence suggests it can decrease parental conflicts and may, through that, subtract kid PTSS. Nosotros do, however, must bear in heed that this multi-wave written report did not include a control group, meaning that more inquiry is needed into the effectiveness of NKM and similar programs targeting parental conflicts in HCD families.

To conclude, this study addressed a gap in our understanding of the intergenerational spillover of HCD by examining how parental conflicts related to kid PTSS, concurrently and longitudinally. It not only demonstrated that parental conflicts in families experiencing a high-conflict divorce are related to child PTSS, but also that changes in parental conflicts may exist related to changes in child PTSS. This study highlights that child PTSS is an important theme inside HCD families and that parental conflicts may play a meaning role into its development. We expect forward to time to come inquiry investigating how PTSS is affected by unlike aspects of the divorce and the behaviors of the parents in HCD families. As such, we can build towards more show-based interventions to protect and support children and aid parents realize positive change.

References

-

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Wedlock and Family, 72, 650–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

-

Anderson, Due south. R., Anderson, S. A., Palmer, K. Fifty., Mutchler, M. S., & Bakery, L. One thousand. (2011). Defining high disharmonize. The American Journal of Family unit Therapy, 39(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2010.530194

-

Asendorpf, J. B., & van Aken, M. A. 1000. (2003). Personality-relationship transaction in adolescence: Core versus surface personality characteristics. Journal of Personality, 71(four), 629–666.

-

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2010). Multiple imputation with mplus. Retrieved on sixth of May 2020 on https://www.statmodel.com/download/Imputations7.pdf

-

Beck, J. A., Anderson, E. R., O'Hara, K. L & Benjamin, Grand. A. H. (2013). Patterns of intimate partner violence in a large, epidemiological sample of divorcing couples. Journal of Family unit Psychology, 27(v), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034182

-

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, Due south., & Blasio, P. D. (2016). Families with singled-out levels of marital disharmonize and kid aligning: Which function for maternal and paternal stress? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 733–745. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10826-015-0261-0

-

Cummings, E. M., Merrilees, C. E., & George, M. Due west. (2010). Fathers, marriages, and families: Revisiting and updating the framework for fathering in family context. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the male parent in kid evolution (5th ed., pp. 154–176). Wiley.

-

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Kliethermes, M., & Murray, L. A. (2012). Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Corruption & Neglect, 36(vi), 528–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.007

-

Davidson, R. D., O'Hara, K. L., & Beck, C. J. A. (2014). Psychological and biological processes in children associated with high conflict parental divorce. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 64(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12015

-

De Smet, O., Loeys, T., & Buysse, A. (2012). Post-breakup unwanted pursuit: A refined analysis of the function of romantic human relationship characteristics. Periodical of Family Violence, 27, 437–452. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10896-012-9437-one

-

El-Sheikh, M., Shimizu, K., Erath, S. A., Phillbrook, L. E., & Hinnant, J. B. (2019). Dynamic patterns of marital conflict: Relations to trajectories of adolescent aligning. Developmental Psychology, 55(viii), 1720–1732. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000746

-

Evans, S. Due east., Davies, C., & DiLillo, D. (2008). Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Assailment and Violent Behavior, 13(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005

-

Fischer, T. F. C., de Graaf, P., & Kalmijn, M. (2005). Friendly and antagonistic contact between former spouses after divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 26(8), 1131–1163.

-

Georgsson, A., Almqvist, K., & Broberg, A. Thousand. (2011). Dissimilarity in vulnerability: Self-reported symptoms among children with experiences of intimate partner violence. Kid Psychiatry & Man Development, 42, 539–556. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10578-011-0231-viii

-

Graham, J. W., Olchowski, A. E., & Gilreath, T. D. (2007). How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science, 8, 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05275435

-

Guttman, 50. (1945). A basis for analyzing test-retest reliability. Psychometrika, 10, 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288892

-

Haj-Yahia, M. 1000., Sokar, S., Hassan-Abbas, North., & Malka, M. (2019). The relationship between exposure to family unit violence in babyhood and post-traumatic stress symptoms in young adulthood: The mediating role of social support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 126–138. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.023

-

Harold, G. T., Elam, K. Chiliad., Neiderhiser, J. Chiliad., Shaw, D. South., Leve, Fifty. D., Thapar, A., & Reiss, D. (2013). The nature of nurture: Disentangling passive genotype-environment correlation from family unit relationship influences on children'due south externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031190

-

Harper, Southward. East., & Fine, M. A. (2006). The effects of involved nonresidential fathers' distress, parenting behaviors, inter-parental conflict, and the quality of male parent-kid relationships on children'southward well-being. Fathering, 4(3), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0403.286

-

Hetherington,E. Yard. (2006). The influence of conflict, marital problem solving and parenting on children's adjustment in nondivorced, divorced and remarried families. Ina. Clarke-Stewart & J. Dunn (Eds.) Families count. Effects on child and adolescent development (pp. 203-237). New York: Cambridge University Press.

-

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Affect of Effect Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004

-

Kalmijn, M. (2015). Father-child relations after divorce in four European countries: Patterns and determinants. Comparative Population Studies, 40(3), 251–276. https://doi.org/x.12765/CPoS-2015-10en

-

Kluwer, E. (2016). Unforgiving motivations amidst divorced parents: Moderation of contact intention and contact frequency. Personal Relationships, 23(iv), 818–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12162

-

Könen, T., & Auerswald, M. (2021). Statistical modeling of latent alter. In: Strobach, T., & Karbach, J. (Eds). Cognitive Preparation. Springer.

-

Lange, A. Thousand. C., Visser, M. K., Finkenauer, C., Kluwer, E. S., & Scholte, R. H. J. (submitted). Families in high-disharmonize divorces: Parent outcomes of No Kids in the Center.

-

Madigan, S., Plamondon, A., & Jenkins, J. M. (2017). Marital conflict trajectories and associations with children's confusing beliefs. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(2), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12356

-

McCoy, Yard. P., George, M. R. W., Cummings, Due east. G., & Davies, P. T. (2013). Constructive and destructive marital disharmonize, parenting, and children'south school and social adjustment. Social Evolution, 22(4), 1-22.

-

Müller, L. R. F., Gossmann, One thousand., Hartmann, F., Büter, K. P., Rosner, R., & Unterhitzenberger, J. (2019). 1-Twelvemonth follow-up of the mental wellness of stress factors in asylum-seeking children and adolescents resettled in Germany. BMC Public Health, xix, 908–919. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7263-half-dozen

-

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

-

Nelson, J. A., O'Brien, M., Blankson, A. North., Calkins, S. D., & Kaene, S. P. (2009). Family stress and parental responses to children's negative emotions: Tests of the spillover, crossover, and compensatory hypotheses. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(5), 671–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015977

-

Nielsen, 50. (2017). Re-examining the inquiry on parental conflict, coparenting, and custody arrangements. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000109

-

Parent, J., Forehand, R., Pomerantz, H., Peisch, V., & Seehuus, M. (2018). Father participation in child psychology research. Journal of Aberrant Child Psychology, 45, 1249–1270. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10802-016-0254-5

-

Perrin, S., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Smith, P. (2005). The Children's Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity every bit a screening musical instrument for PTSD. Behavioural and Cerebral Psychotherapy, 33, 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465805002419

-

Ponnet, K., Mortelmans, D., Wouters, E., van Leeuwen, Kl., Bastaits, K., & Pasteels, I. (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers' and fathers' parenting. Personal Relationships, 20(two), 259–276. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.ten

-

Qu, Fifty., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Kaspiew, R., & Dunstan, J. (2014). Post-separation parenting, property and relationship dynamics after five years. Australian Institute of Family Studies.

-

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure assay. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514. https://doi.org/x.1007/BF02296192

-

Smyth, B. M., & Moloney, L. J. (2019). Post-separation parenting disputes and the many faces of high conflict: Theory and research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(one), 74–84. https://doi.org/x.1002/anzf.1346

-

Sweeper, S., & Halford, Thou. (2006). Assessing adult adjustment to relationship separation: The psychological adjustment to separation test (By). Periodical of Family unit Psychology, 20(4), 632–640.

-

Target, M., Hertzmann, L., Midgley, Northward., Casey, P., & Lassri, D. (2017). Parents' experience of child contact within entrenched conflict families following separation and divorce: A qualitative report. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 31(ii), 218–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2016.1268197

-

Ter Voet, M. (2019). Scheidingen 2018. Gerechtelijke procedures en gesubsidieerde rechtsbijstand. [Divorces 2018. Judicial procedures and subsidized judicial assistance]. Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum.

-

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, 1000. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting, 10(4), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2010.492040

-

Tully, L. A., Piotrowska, P. J., Collins, D. A. J., Mairet, G. South., Blackness, N., Kimonis, Eastward. R., & Dadds, Yard. R. (2017). Optimising child outcomes from parenting interventions: Fathers' experiences, preferencs and barriers to participation. BMC Public Health, 17, 550–564. https://doi.org/x.1186/s12889-017-4426-1

-

Van der Ploeg, E., Mooren, T., Kleber, R. J., van der Velden, P. G., & Brom, D. (2004). Construct validation of the Dutch version of the impact of event calibration. Psychological Assessment, sixteen(i), sixteen–26. https://doi.org/ten.1037/1040-3590.xvi.1.16

-

Van der Wal, R. C., Finkenauer, C., & Visser, K. (2019). Reconciling mixed findings on children's adjustment following high-conflict divorce. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 28, 468–478. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10826-018-1277-z

-

Van Dijk, R., van der Valk, I. E., Deković, Chiliad., & Branje, Southward. (2020). A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: Examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clinical Psychology Review, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101861

-

Van Eldik, W. M., de Haan, A. D., Parry, 50. Q., Davies, P. T., Luijk, M. P. C. M., Arends, L. R., & Prinzie, P. (2020). The interparental relationship: Meta-analytic associations with children's maladjustment and responses to interparental conflict. Psychological Bulletin, 146(seven), 553–594. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000233

-

Verlinden, E., van Meijel, Due east. P. Thou., Opmeer, B. C., Beer, R., de Roos, C., Bicanic, I. A. E., & Lindauer, R. J. 50. (2014). Characteristics of the children'due south revised bear on of upshot calibration in a clinically referred Dutch sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(three), 338–344. https://doi.org/ten.1002/jts.21910

-

Visser, Thousand., van Lawick, J., Stith, S. Yard., & Spencer, C. (2020). Violence in families: Systemic practise and research. In: Ochs, M., Borcsa, M. & Schweitzer, J. (eds.), Linking Systemic Research and Practice – Innovations in paradigms, strategies and methods. (European Family Therapy Association Series, Volume four). Springer International.

-

Visser, Thou. & J. Van Lawick (2021). Group Therapy for Loftier-Conflict Divorce: The 'No Kids in the Middle' Intervention Program. Routledge.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all parents and children for their participation in the study and the participating mental health institutions for supporting data collection and their engagement for helping these families. We likewise give thanks Kim Schoemaker and Annelies de Kruiff for their invaluable piece of work in the data collection, Margot van der Wart for creating fourth dimension and infinite to support the scientific research in a clinical setting and Marc Delsing for his advice on the statistical analyses. We would too like to thank Justine van Lawick, Erik van der Elst, Elisabeth van der Heide, Wendy de Visser, Flora van Grinsven, and Jeroen Wierstra for their suggestions and ideas in interpreting the results.

Funding

This study was supported by Kenter Jeugdhulp and de Viersprong too as by a grant from Stichting Achmea Slachtoffer en Samenleving.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was provided by the institutional inquiry ethics committee (VCWE-2015–112) from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Disharmonize of Interest

One thousand. M. Visser co-adult the intervention No Kids in the Middle.

Boosted information

Publisher'due south Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long every bit you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and betoken if changes were made. The images or other third party cloth in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this commodity

Cite this article

Lange, A.M.C., Visser, M.M., Scholte, R.H.J. et al. Parental Conflicts and Posttraumatic Stress of Children in High-Conflict Divorce Families. Journ Child Adol Trauma (2021). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s40653-021-00410-9

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00410-9

Keywords

- High-conflict divorce

- Parental disharmonize

- Interparental contact

- Post-traumatic stress

- Intervention

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40653-021-00410-9

0 Response to "Can a Child Get Ptsd From Multiple Divorces in Family"

Postar um comentário